Understanding Maskirovka: Russia's Use Of Deceit In War And Foreign Policy

Maskirovka is an intricate combination of concealment, deceptive maneuvers, denial, and disinformation designed to maintain plausible deniability while conducting subversive activities.

Deceit is a defining characteristic of Russian intelligence and military operations. This was evident in the lead-up to the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian war, where President Vladimir Putin and Russian diplomats launched a multi-faceted campaign to convince the world that Russia would not invade Ukraine.

This was also visible in 2013, when Russian intelligence agencies planted news stories alleging that the National Security Agency (NSA) was spying on German Chancellor Angela Merkel, aiming to provoke a rift between the United States and its European allies.

Such deception is part of a Russian tactic known as “Maskirovka,” the name of which is derived from the Russian word for “disguise” or “mask.”

Maskirovka is an intricate combination of concealment, deceptive maneuvers, denial, and disinformation designed to maintain plausible deniability while conducting subversive activities.

To be better equipped against Russia’s use of this tactic, it is vital to understand Maskirovka’s historical origins, guiding principles, characteristics, and how it was applied during peacetime in the past. The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis serves as a helpful case study for understanding the peacetime deployment of Maskirovka.

Historical Uses of Deception in Warfare

Deception as a tool of warfare goes far back in history before the origins of Russia.

In his seminal book on warfare, “The Art of War”—written between 475 and 221 BC—Chinese philosopher Sun Tzu wrote, “A military operation involves deception. Even though you are competent, appear to be incompetent. Though effective, appear to be ineffective.”

Tzu further wrote that “[t]he purpose of deception as a strategic art… is to prevent adversaries from using their aggressive and defensive capacities accurately.”

The first known use of deception—of the likes of Maskirovka—in Russian history was by Prince Dmitry Donskoy of Muscovy in the 1380 Battle of Kulikov Field. In that battle, 50,000 Russian soldiers defeated a horde of 150,000 Tatar-Mongolian troops fielded by Khan Mamay near the Don River.

Key to the surprising defeat of the Tatar-Mongol horde was Donskoy’s decision to hide a group of soldiers in a forest near the battlefield, instructing them to mount a blitz on the unsuspecting Tatar-Mongol army while it engaged conventional unconcealed Russian soldiers.

The move helped change the tide of the battle, precipitating the end of Mongol dominance over the Slavs and early Russia. The battle and the tactics involved were so decisive in early Russian history that they are often cited in present-day Russian military cadet schools.

The Development of Modern Maskirovka

By 1904, the Russian Army had its own military school for deception—the Higher School of Maskirovka. Though disbanded later in 1929, the school provided fertile ground for Maskirovka’s foundational concepts and developed manuals that future generations of Russian military and counterintelligence officers would study. The years between 1904 and 1929 saw the early theorization of Maskirovka in Russia and what would then become the Soviet Union. A 1924 Soviet directive addressed to higher commands instructs military leaders that operational deception should be “based upon the principles of activity, naturalness, diversity, and continuity and includes secrecy, imitation, demonstrative actions, and disinformation.”

The Second World War would see the large-scale deployment of Maskirovka by the Soviet Union, primarily in the 1939 Battles of Khalkhin Gol against Japan; the 1942 First Rzhev–Sychyovka Offensive Operation; the 1942-1943 Battle of Stalingrad, chiefly in Operation Uranus; the 1944 Battle of Kursk; and, the 1944 Operation Bagration. Over this time and during the early and middle years of the Cold War, the theories underlying Maskirovka would undergo significant evolutions.

Impact of the Cold War on Maskirovka

By 1978, Maskirovka, or strategic deception, moved from being strictly confined to the military dimension to encompass the social, political, diplomatic, and economic dimensions. A 1978 Soviet Military Encyclopedia describes Maskirovka as a tactic “carried out at national and theater levels to mislead the enemy regarding the political and military capabilities, intentions, and timing of actions. In these spheres, as war is but an extension of politics, it includes political, economic, and diplomatic measures as well as military.” This transformation of Maskirovka from a purely military tactic to a multi-dimensional practice is noteworthy, for it indicates how much the Cold War had transformed Maskirovka.

With the start of the Cold War, Russia or the Soviet Union’s threats were not hot targets it was actively in conflict with, but cold targets. The goal for Soviet intelligence in the Cold War, therefore, was to undertake espionage and subversive activities short of armed conflict while maintaining plausible deniability, while the goal of Soviet counterintelligence was to mislead adversaries and distort the information hostile intelligence agencies received of Soviet activities and intent. The change in goals helped shape Maskirovka into its present-day form, particularly in the counterintelligence dimension, where it is used to confuse, mislead, obstruct, and distort foreign intelligence gathering of Soviet “plans, objectives, and strengths or weaknesses.”

With the fall of the Soviet Union, the USSR’s predecessor, Russia, will continue to practice this present-day form of Maskirovka in the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea, and the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War.

Forms of Maskirovka

Defense researcher Charles Smith identifies five contemporary forms of Maskirovka: Concealment (Sokrytiye), Imitation (Imitatsiya), Simulation (Simulatsiya), Disinformation (Dezinformatsiya), and Demonstrative Maneuvers (Demonstrativnyye manevry).

Concealment involves making efforts to prevent enemy intelligence from detecting troop movements, military plans, or weapons production. This can be achieved through aggressive means, such as vetting personnel and intercepting unauthorized aircraft, or passive means, like manufacturing tanks in automobile factories.

Imitation involves setting up decoys and dummies to deceive enemy forces about troop build-ups or attack directions. This tactic dates back to World War II when Soviet troops used dummy tanks and decoy bridges to mislead German forces. Simulation, closely linked to imitation, includes creating fake artillery batteries and anti-aircraft batteries, simulating their real-life counterparts through smoke and noise.

Demonstrative Maneuvers involve actual equipment and troops conducting maneuvers intended to create uncertainty and divert enemy attention from the main thrust of an operation. These actions were evident in the lead-up to the 2022 Russo-Ukraine war, where military build-ups and exercises heightened tensions.

Disinformation, commonly used in offensive operations, involves publishing misleading maps, hacking navigation systems, and planting false stories to misguide the enemy.

Principles of Maskirovka

The five forms of Maskirovka are guided by the practice’s four foundational principles: Activity, Plausibility, Variety, and Continuity.

Activity dictates that all forms of Maskirovka must be aggressive and active to trick the enemy into falsely assessing Russian capabilities and movements.

Plausibility dictates that all deceptive maneuvers must appear realistic to enemy intelligence agencies, posing a convincing trap.

Variety requires counterintelligence officers to avoid repetitive patterns that could arouse suspicion and continually change tactics to maintain deception.

Continuity emphasizes the need to sustain deception throughout an operation. Failure to adhere to this principle, as was the case during the Soviet missile transfers to Cuba that triggered the Soviet Missile Crisis, can lead to the exposure of the operation.

Cuban Missile Crisis - Case Study

The Soviet Union’s transfer of nuclear-capable SS-4 and SS-5 surface-to-surface missiles to Cuba is a case where Soviet counterintelligence officers successfully deployed Maskirovka to prevent the US and other Western powers and their intelligence agencies from learning about the weapons transfer for a long while.

The US would, however, eventually learn about the transfer, leading to the Cuban Missile Crisis, which would see the US impose a unilateral naval blockade of the island nation and the world’s two superpowers moving to the brink of atomic war.

Absolute Secrecy

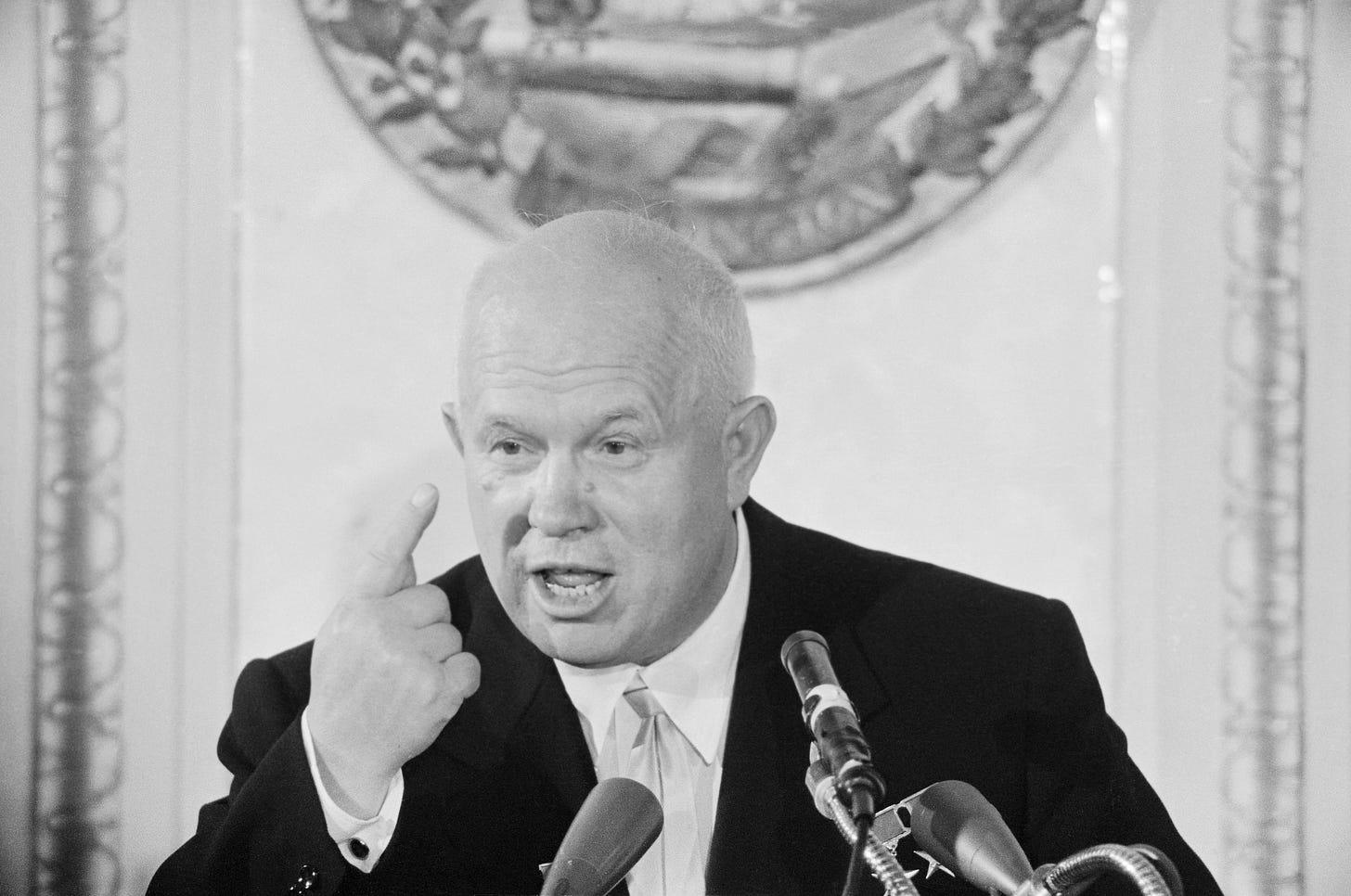

According to retired Central Intelligence Officer and intelligence studies researcher James H Hansen, the initial plans for the missile transfer began when Soviet Union Secretary General Nikita Khrushchev ordered the placement of the missiles in absolute secrecy.

Following Khrushchev’s order, only four generals and one colonel were appointed by the Soviet General Staff to plan the operation without Washington being made aware of it. The mission’s planners were so careful about operational security that no secretaries were involved in typing out the plan—it was written entirely by a colonel with good handwriting.

The decision to move the missiles to Cuba was a momentous one, for, from the perspective of those who made it, it granted the Soviet Union unprecedented access and distance from the mainland US, upsetting the strategic balance that hitherto existed between the two powers.

Winter

To prevent foreign intelligence agencies and Soviet citizens from discovering the operation’s goals, the General Staff named the Cuban missile transfer operation Operation Anadyr after the river Anadyr, which flows into the Bering Sea near Alaska. The reasoning behind the choice of name was to trick low-level officers and foreign spies into assuming that the movement of ammunition and missiles was to the far north of the USSR and not to Cuba.

To solidify the deception, troops participating in the Cuban missile transfer were told that they would be moving ICBMS to the Arctic Island of Novaya Zemlaya—a former nuclear weapons test site. Soviet soldiers were equipped with winter clothing such as skis, felt boots, and fleece-lined parkas to make the ploy convincing.

The military deception was also accompanied by diplomatic deception. Soviet interaction with Cuban officials on the missile transfer happened under the guise of discussions between “agricultural” and “irrigation” experts. When the time came for hardware transfers, they were done in absolute secrecy, out of eight ports shut off from the outside world while the ships were loaded: Kronstadt, Liepaya, Baltiysk, Murmansk, Sevastopol, Feodosiya, Nikolayev, and Poti.

Obfuscation

None of the ships’ crew were allowed to correspond with the outside world, maintaining absolute secrecy. Special measures such as boarding up equipment with planks were undertaken to prevent foreign intelligence from learning of the real nature of the ship’s cargo. Furthermore, a lockdown was imposed on these port cities to control the movement of people in and out to that end. Only when the ships were boarded were the crew notified of the destination.

On the way to Cuba, several deception measures were employed to prevent foreign intelligence from learning of the missile transfer. This included declaring Conakry, Guinea, as a destination and protesting American reconnaissance attempts on the ships as harassment.

Finally, once the ships were in Cuba, their contents were declared to be fertilizer and transported in unmarked vehicles.

Damage Control

Cuban officials, however, through their negligence, betrayed the secrecy of the operation. Information on the missiles began leaking to Washington via the Cuban émigré community, who served as sources of valuable human intelligence on the island.

This should have meant that the cover on the missile transfers was blown.

Not so quickly—Cuban and Soviet officials swiftly deployed Disinformation (Dezinformatsiya) tactics to undermine the trust Washington had in the testimonies of the Cuban émigré community by feeding them specially prepared information comprised of half-truths so that even should they share the whole truth, it would be discredited.

The disinformation spread was so bizarre that the US intelligence community became very wary of trusting the émigré community on their accounts of Russians in Cuba.

Cover Blown

The US suspected Soviet activity on the island but lacked concrete evidence.

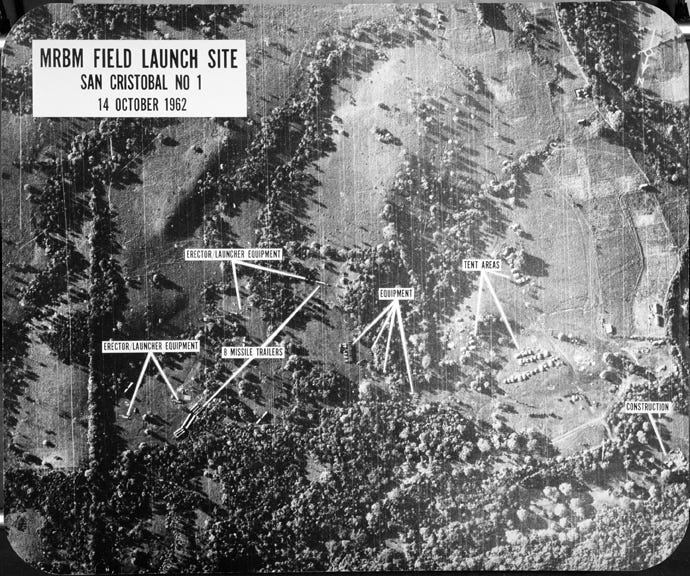

American suspicions, however, would be finally confirmed thanks to a U-2 spy plane mission on October 14th, 1962.

Pilot Major Rudolf Anderson Jr., who flew that day, captured clear images showing construction sites for medium-range and intermediate-range ballistic nuclear missiles (MRBMs and IRBMs). The photographs were rushed back to the US and analyzed. The results confirmed Washington’s fears and led to President John F. Kennedy taking actions that led to the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Reasons For Failure

There are two main reasons why the Soviets couldn’t completely hide the missiles during the Cuban Missile Crisis—issues with concealment and continuity.

While Maskirovka employed concealment tactics like secrecy during loading and travel, hiding operational missile sites proved difficult. Missiles are large and require significant infrastructure for launch and support. Building these sites quickly and keeping them entirely hidden, especially from high-altitude reconnaissance, was a challenge.

Maskirovka emphasizes continuity, meaning deception needs to be maintained throughout the operation. The Soviets initially maintained secrecy well. However, maintaining the deception became impossible once the missiles arrived in Cuba and construction began on launch sites. The physical presence of these large structures became a telltale sign, and the U-2 spy plane was able to capture photographic evidence.

Maskirovka Today

Maskirovka is not merely a relic of the past but a dynamic and evolving practice that continues to shape the outcomes of Russia’s conflicts today. In contemporary conflicts, Maskirovka is evident in various operations, from Moscow’s stealthy annexation of Crimea in 2014 to the strategic maneuvers leading up to and during the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War.

The tactic has survived the test of time, adapting to new technologies. For instance, the use of cyberattacks to disrupt enemy communication systems, the deployment of decoys to mislead satellite reconnaissance, and the spread of fake news to influence public opinion on social media all illustrate how Maskirovka can and is used in modern days both during peace and war.

References/Further Reading

Ash, Lucy. “How Russia Outfoxes Its Enemies.” BBC News, January 29, 2015, sec. Magazine. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-31020283.

Dey, Aninda. “Putin Masters Maskirovka in Ukraine, Bamboozles Biden.” The Times of India. Accessed December 13, 2022. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/words-worth/putin-masters-maskirovka-in-ukraine-bamboozles-biden/?source=app&frmapp=yes.

Glantz, David M. Soviet Military Deception in the Second World War. Routledge, 2012.

Hansen, James. “Soviet Deception in the Cuban Missile Crisis.” Studies in Intelligence 46, no. 1 (2002): 20.

Iancu, N., A. Fortuna, and C. Barna. Countering Hybrid Threats: Lessons Learned from Ukraine. IOS Press, 2016.

Kowalewski, Annie. “Disinformation and Reflexive Control: The New Cold War.” Georgetown Security Studies Review, February 2, 2017. https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/2017/02/01/disinformation-and-reflexive-control-the-new-cold-war/.

Maier, Morgan. A Little Masquerade: Russia’s Evolving Employment of Maskirovka. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: School of Advanced Military Studies at United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2016. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1022096.pdf.

Quinn, Melissa. “Russian Ambassador Insists Kremlin Has ‘No Such Plans’ for Invading Ukraine despite Troop Build-Up.” CBS News Face The Nation. Accessed December 13, 2022. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/russia-ukraine-ambassador-anatoly-antonov-no-such-plans-invasion-face-the-nation/.

Rid, Thomas. Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare. Profile Books, 2020.

Smith, Charles. “Soviet Maskirovka.” Airpower Journal 2, no. 1 (Spring 1998). https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ/journals/Volume-02_Issue-1-4/1988_Vol2_No1.pdf.

Thomas, Timothy. “Russia’s Reflexive Control Theory and the Military.” The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 17, no. 2 (June 1, 2004): 237–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13518040490450529.

Tzu, Sun. The Art of War. Translated by Thomas Cleary. Abridged edition. Boston, Mass London: Shambhala, 2005.